Patterns of the Infinite: Repetition, Silence and Time in the Search for Meaning

Introduction

The human experience is marked by rhythms—patterns that repeat, moments of stillness, and the inexorable flow of time. These elements, when approached with intention, become more than mere circumstances of existence. They transform into tools for introspection, growth, and the search for meaning. From the meditative practices of the Desert Fathers in the barren wilderness to the quiet rituals of daily life, repetition, silence, and time are recurring themes in humanity’s quest to understand itself.

Yet, these tools are not bound by religion or doctrine. They are universal, transcending specific spiritual traditions to offer a lens through which we can explore the essence of the human condition. This essay examines how repetition, silence, and time intertwine to reveal the depths of human experience, reflecting the struggles, joys, and mysteries of existence.

Repetition as Ritual

Repetition is often seen as mundane—daily routines, habitual tasks, the cyclical nature of seasons. Yet within its constancy lies profound potential. Consider the repetitive movements of a potter shaping clay on a wheel. To an observer, the circular motions may seem monotonous, but for the potter, each rotation refines the vessel, revealing its form through persistence and care.

In spiritual traditions, repetition is a tool for transcendence. The Desert Fathers, early Christian ascetics who sought solitude in the Egyptian wilderness, often engaged in repetitive prayers or chants, finding that the act of repetition quieted the mind and opened pathways to clarity. Similarly, in Zen Buddhism, the act of sweeping a floor or arranging flowers is a practice of mindfulness, where the repetitive act itself becomes a meditation.

Beyond the spiritual, repetition shapes our personal lives. The rituals of morning coffee, a daily walk, or even the comforting repetition of familiar music ground us in the present. But repetition also carries a shadow. The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche’s concept of eternal recurrence challenges us to consider: if we were to live our lives on an infinite loop, would we embrace or dread it? Repetition, then, becomes both a mirror and a test—a way to confront the patterns we choose to live by.

Silence as a Mirror

In a world saturated with noise—auditory, digital, and emotional—silence feels increasingly rare. It is often dismissed as empty or uncomfortable, yet it holds immense power. The poet Rainer Maria Rilke wrote of silence as “the pause in us as we taste what we have spoken.” 1 In this way, silence is not absence but fullness—a space where meaning takes shape.

Consider silence not only as a pause but as a phenomenon of scale. The artist Marcel Duchamp coined the term inframince to describe immeasurably subtle phenomena, such as “the space between the recto and the verso” 2 of a sheet of paper. Silence, too, can be seen as inframince—occupying the liminal space between sound and thought, a quantum threshold where presence dissolves into absence. It is a whisper at the edge of articulation, at once infinitesimally small and cosmically vast. This duality invites us to experience silence as both finite, contained within a moment, and infinite, opening into the void beyond what words can hold.

The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, in the final proposition of his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, offers a similar reflection: “What we cannot speak of we must pass over in silence.” 3 For Wittgenstein, silence acknowledges the ineffable—the truths, emotions, and experiences beyond the reach of language. Here, scale matters again: silence is both a boundary that limits us and a boundlessness that invites exploration. Duchamp’s inframince and Wittgenstein’s silence converge in their shared recognition of the invisible dimensions of existence.

However, silence is not always gentle. It can be oppressive, as in the silence of loneliness or exclusion. Yet even these silences teach us. The French philosopher Simone Weil described waiting in silence as an act of faith, a posture of openness to the unknown. 4 For the Desert Fathers, silence was both a practice and a struggle, a means to confront their inner turmoil and hear what lay beyond it.

In human relationships, silence is equally complex. A shared silence between close friends or lovers can speak volumes, fostering intimacy without words. Conversely, silence in conflict can wound, leaving things unsaid. These dualities remind us that silence is a dynamic force, capable of both healing and harm.

Time as a Teacher

Time is the most elusive of the three themes—an invisible current that defines our existence. We measure it with clocks and calendars, yet we experience it subjectively, stretched or compressed by emotion and memory. Marcel Proust, in his monumental novel In Search of Lost Time, explores how a single moment—a taste of a madeleine dipped in tea—can collapse the barriers of past and present, revealing the richness of a life once thought forgotten.

For the Desert Fathers, time was an opponent to be transcended. Days stretched endlessly in the desert, marked only by the rising and setting sun. This confrontation with unstructured time forced them to wrestle with their own mortality and purpose. Today, we face a different challenge: time seems to rush forward, fractured by deadlines and distractions. Yet moments of stillness—whether in meditation, art, or nature—can expand time, offering glimpses of eternity.

Consider the timelessness of the ocean. The waves repeat endlessly, echoing the theme of repetition, yet they are never the same. To sit by the sea is to witness time’s paradox: the constant motion of the present and the ageless vastness of the horizon. Such moments remind us that time is not merely something to measure but something to experience deeply.

When Repetition, Silence and Time Meet

Repetition, silence, and time do not exist in isolation; they are interwoven, creating a tapestry that reflects the complexity of being human. The repetitive cycles of nature—day and night, the seasons—are experienced differently depending on the silence or noise within us and our awareness of time’s passage.

Take, for example, the act of tending a garden. The gardener returns daily, repeating the same tasks—watering, weeding, pruning—each action small yet essential. Silence often accompanies the work, broken only by the rustle of leaves or the chirp of a bird. Over time, the garden transforms, though the growth is imperceptible from one day to the next. The interplay of repetition, silence, and time becomes visible in the blooms of spring or the ripening of fruit, a testament to patience and care. The process mirrors life itself: an accumulation of small acts shaped by the rhythms of nature and the quiet persistence of time.

In our lives, too, these elements converge. A daily walk in silence becomes a meditation on the passing of time. A quiet moment at dawn reveals the beauty of repetition in the natural world. These experiences invite us to reflect: How do we engage with these forces? Do we resist them, or do we embrace their capacity to shape and transform us?

Conclusion

Repetition, silence, and time are more than abstract concepts; they are the rhythms of life itself. Whether in the solitude of the desert, the noise of the modern world, or the quiet rituals of our days, these themes offer ways to explore the depths of the human condition. They constrain and liberate, comfort and challenge, obscure and reveal.

Ultimately, to embrace repetition, silence, and time is to engage fully with the mystery of existence. It is to recognize that in the patterns of the infinite, we find not answers, but meaning—a meaning that unfolds not in a single moment, but over a lifetime.

© Chris Tosic,

January 2025

Footnotes

1. Rainer Maria Rilke on Silence Rilke, Rainer Maria. Letters to a Young Poet. Translated by Stephen Mitchell, Modern Library, 1986, Letter 6.

2. Marcel Duchamp’s Concept of Inframince Duchamp, Marcel. The Writings of Marcel Duchamp. Edited by Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson, Da Capo Press, 1973, p. 194.

3. Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Proposition on Silence Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Translated by C. K. Ogden, Kegan Paul, 1922, Proposition 7.

4. Simone Weil’s Reflection on Silence Weil, Simone. Waiting for God. Translated by Emma Craufurd, Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2009, p. 101.

Download a PDF here.

Notes on painting

One of my main concerns within these paintings is to move away from tired and conventional tropes of personal expression. I do this by using similar – though not identical – compositional structures. Basic design patterns are layered and developed according to aleatory principles which remain fully open yet allow subjective decisions to override visual imbalance or other concerns I feel need to be addressed. The canvases are of a uniform size and may be exhibited singly or in carefully arranged grids.

The use of repetition is a fundamental part of my painting process, yet despite having an “automated” look, these works are all hand-made. I employ the banality of repetition as a means by which I can further avoid making works that are too close to the clichés of Western ideas of ego and self. There is a strong sense of the mechanical about these paintings, though this is countered using playful juxtapositions which push and pull on the flat surface to form consonance and dissonance in equal amounts.

Part of my chance-based methodology is the use of unmixed colours. Furthermore, these colours are applied in a way that deliberately avoids painterly gestures. Also, through a combination of masking-out and repeated paint layers, raised edges develop, making the final surface a complex arrangement of shapes and patterns that operate in slight relief.

The titles for these images are created by cut-up processes or borrowed from colour taxonomy systems. This interplay of image and title encourages an “open ended” experience of the work that is hopefully unique to every observer, so that what appears on the surface as contradictory or inexpressive becomes pregnant with possibilities.

In the end the paintings are intended to be “elliptical” and entirely self-sufficient, standing for nothing but themselves.

Chris Tosic with additional edits by Peter Suchin

2023

Press

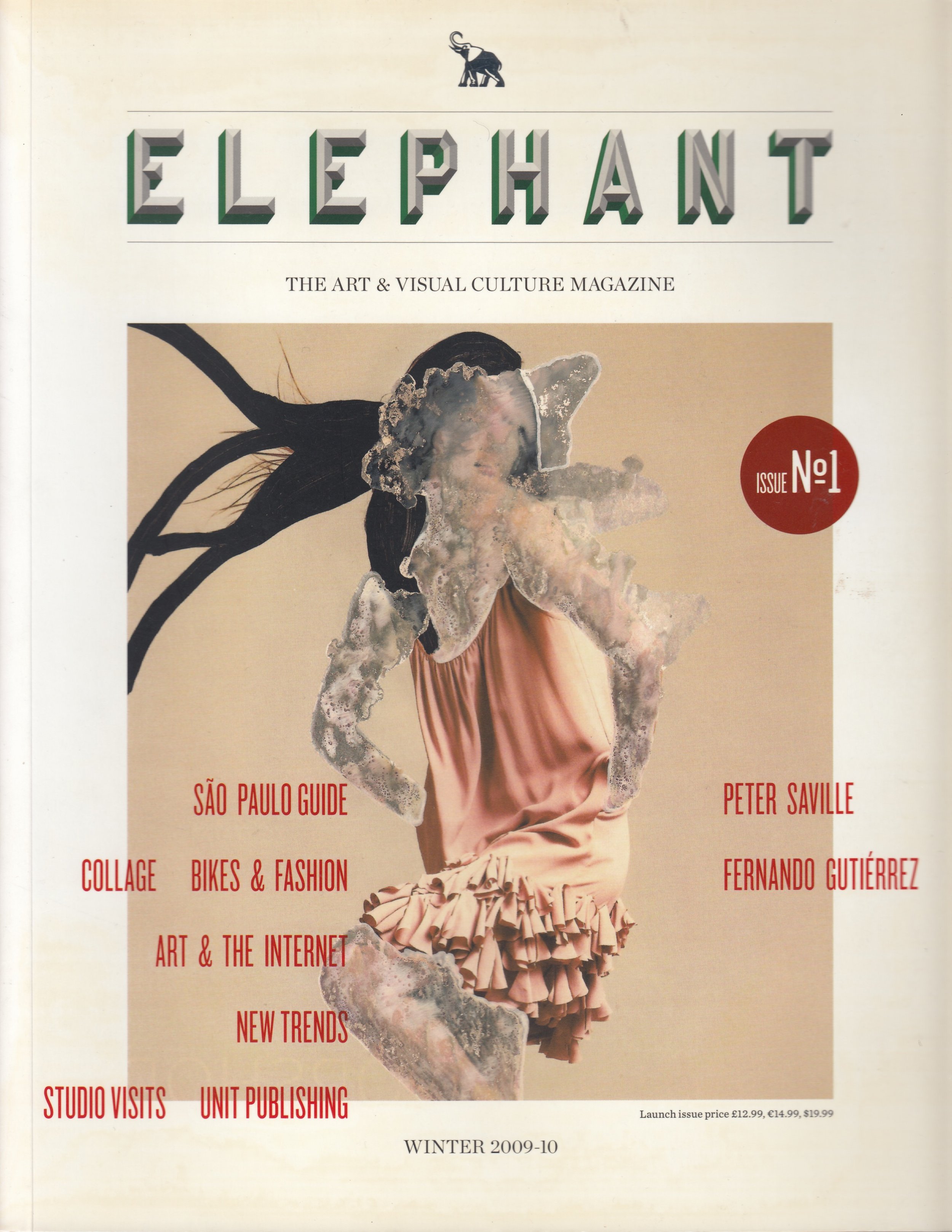

Elephant Magazine: Issue One

Interview with Richard Brereton

2009 – 10

Download a PDF here.